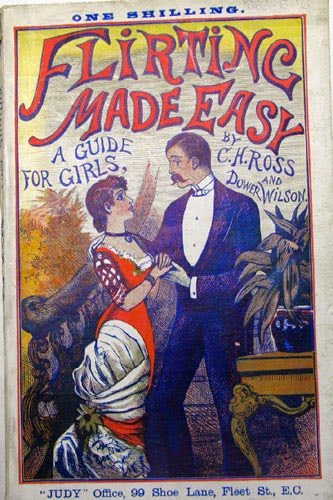

"All girls flirt with soldiers: they can't help it, no more can the soldiers, or they would.Although "Flirting Made Easy: A Guide for Girls" (1882) is a little before my time period, I just couldn't resist this tongue-in-cheek etiquette guide by a man who is "not prepared to believe that any male thing could possibly be 'disgusted' with the flirtings of a nice girl, unless the nice girl happened to belong to him, and he had to sit out in the cold whilst the flintiness went on with other fellows."

Cornets or Ensigns, Lieutenants, and Captains are flirted with the most. Only very bold girls indeed would try to flirt with a General!" Flirting Made Easy by C.H. Ross

Although the eBook is available for free on Google Play, I haven't been able to find a single review, and it appears few people read it at all nowadays. For those who do, it is a passing fancy, interesting only in the pursuit of one subject or another that it touches on in its pages. I write this blog post hoping to change that.

Flirting Made Easy tells us a lot about late-Victorian slang, and perceptions of gender. A "deuce" is like cool or swell. "Bosh" and "a jolly crammer" are words for lies. And it's not bosh that Ross thought "Bar Young Ladies" were deuce.

The Bar Young Lady is essentially a modern institution, called into life by a general demand. She in a great measure owes her existence to Charles Dickens, who, in his Christmas Number called "Mugby Junction," was possibly the first to print a diatribe on the iniquities of the railway station sandwich. Long before that everyone had suffered, and, it is only right to ass, suffers still; but great reforms in this particular were at the time talked of, and in some particulars actually effected. One or two enterprising firms took possession of the refreshment-rooms, and handsomely decorated them, and the Bar Young Lady was born and flourished.

Hitherto there had been barmaids and bar-girls, waitresses and female attendants; but these gave place to the Bar Young Lady, and she was a big success. She came and saw and conquered. She not infrequently married money.

She was no longer of that sisterhood which were only Pollies, and Mollies, and Mary Annes. She was Miss Pamela Andrews, Miss Clarissa Richardson, Miss Barlow, Miss Sandford, and Miss Merton - (mark well the nomenclature) - not Fitz-Talbot, De Vere, or Montmorency. There was and is an intensity of propriety and respectability about the Bar Young Lady that is absolutely crushing.What is in a name? These forms of address have so much meaning, even surnames connote class. To many of Ross's peers calling a lady by her first name meant you intended to marry her. Victorian London was also an extremely classist society, and the treatment of lower-class women differed from the treatment of "respectable" women. Ross inadvertently identifies this and the changing expectations of how working women should be treated in his discussion of the "Bar Young Lady."

While Ross's work is intended to be humorous, I can not overlook the fact that the book claims to be "A Guide for Girls," but rarely speaks to women. On many occasions, Ross directly addresses his male friends. For the most part, Flirting Made Easy is a collection of anecdotes, through which Ross pretends to instruct women.

By way of example, I will leave you with a short chapter from Flirting Made Easy that is most appropriate for this blog.

AUTHORESSES CONSIDERED AS WOMEN,

AND ONE PARTICULAR LITERARY LOVE AFFAIR

THAT CAME TO NOTHING

Shy authors are probably to be found here and there, but they are not plentiful. There are authors who have not much to say for themselves in the society of other authors, but their silence must not always be attributed to excessive modesty. Occasionally and author sits apart and smolders. Take them altogether, they have a pretty good opinion of themselves, and the shyest one out, most likely, harangues his poor suffering wife upon the subject of himself and works until she gasps again - or gapes.

I do not, however, speak from experience. The lady members of my household have assured me again and again that they are only too happy to listen to me. Some men have a way of imparting information that carries their readers with them. For my part, I know nothing more delightful than to listen to a witty man with a brilliant flow of language, and this opinion is shared by my sisters, my cousins, and my aunts.

But I do not want to talk about authors. It is rather authoresses I would converse. I have since childhood's hour had a burning desire to make the acquaintance of literary ladies. I should like to have known Miss Martineau. "Is it a man or a woman, or what sort of animal is it?" the good dame said who met her at Ambleside. "There she came, stride, stride - great heavy shoes, stout leather leggings on - and a knapsack on her back, and they say she mows her own grass and digs her own cabbages and potatoes." And poor L.E.L, "a comely girl with a blooming complexion," who, in spite of her sentimental verse, was fond of "a little quiet dance," and with opinions wild as the wind, flying from subject to subject, lighting up each with wit, "fairly talked herself out of breath." "Hey!" cried Ettrick Shepherd when he met her, "but I didna think ye's bin sae bonnie."

And Maria Edgeworth, whom Byron described as "a nice little unassuming Jeanie Deans-looking body, who one would never have guessed could write her name." And Charlotte Bronte, who, according to a writer in the "Quarterly," was "a person who, with great mental powers, combined a total ignorance of the habits of society, a great coarseness of taste and a heathenish doctrine of religion." And Mrs. Hemans, whose "silken hair unbraided flowed around her like a veil." and the Countess of Blessington, whose person, when N.P. Willis saw her, "preserved all in the fineness of admirable shape," and she wore a dress of blue satin "cut low and folded across her bosom in a way to show to advantage the sculpture-like curve and whiteness of a pair of exquisite shoulders."

I should have been a bit afraid of "Holy Hannah," as Walpole calls Mrs. More, and I fancy Anne Radcliffe might have frightened me, though I can find nothing about her personal appearance, and both ladies were rather before my time. But I would willingly have made a little journey to see the authoress of the "Simple Story," whose own account of herself is here before me. Her age, she says, was then a little over thirty. She was above the middle height - rather tall. Her figure was handsome, but a little too stiff. "Shape, rather too fond of sharp angles. Bosom, none." Her skin, by nature fair, but a little freckled. Her hair, a sandy brown. Her face, beautiful. Her countenance, full of spirit and sweetness, "excessively interesting, and, without indelicacy, voluptuous." And her dress, "always becoming; and very seldom worth so much as eightpence." With the figure she describes she might possibly have had threepence to spare if she bought glazed calico.

It might be urged by an authoress reading these remarks that I make small mention of the mental qualities of most of the ladies I have alluded to. Well, I plead guilty. So many other fellows have already said such a lot upon the subject, and when I think of authoresses, I chose to think of them as women, which to the best of my belief, most of them are. Why, I have heard of one was married twice.

There is an enthusiasm about the adorable sex when it goes in for anything out of the beaten track. When it writes books, or paints pictures, or makes speeches, or gets itself appointed drum-major to a "Salvation Army," that is delightful to contemplate; but it has then not time for love-making nonsense.

Where, I have often asked myself, do lady novelists go for their heroines? The heroine of the lady novelist is, as a rule, the very reverse of her own self, if we may believe the nasty cynical male writing things; but, if this be the case, great heaven! where are the illusions of my youth? Is everything different to what it is said to be? Is nothing properly described? As Truthful James asks: "Do I sleep? do I dream? do I wonder and doubt? Are things what they seem, or are visions about? Is our civilization a failure, or is the Caucasion played out?" I don't go so far as to say that I entirely follow T.J. In these observations, but I ask, Are we being deceived by the women who write of women? Are not any of them taken from real life? Do even authoresses, like the rest of their sex, join issue against the unmarried male creature in one great sham? I feel frightened when I think of it.

Now there is my good friend Boodler, novels, dramatist, poet, critic, and writer of slashing leaders for a great daily. In a print explosive, in private life of the mildest, wearing spectacles. Well, he is an honored guest at the house of a nobleman with whom I have the honor to be acquainted, and of one of that nobleman's daughters was he deeply enamored. Deceived by the graciousness of the dear girl's manner, an impulsiveness amounting almost to gushingness, poor Boodler fancied that he was not wholly indifferent to her. Gently would she lead him forth and trot him out, and he would prattle a long while at a time - with clasped hands and great grey eye, gazed into his spectacle-glasses and seemed to drink in every utterance.

One day, the wretched man, thus deceived by appearances, and finding himself alone with her, ventured upon tenderness. Happily for him, he was more than usually vague, and preoccupee. She did not understand him, but when he began offering the devotion of a life, she thought - the artful little thing! - she saw a chance she had long been lying in wait for, and proposed that he should exert his influence with the publishers to sell her first novel. Then, right off and without taking a breath, she told him the whole of the plot, the narration of which occupied more than three quarters of an hour.

Utterly crushed, poor Boddler had not the presence of mind to dictate terms, which in his place some villain might have done. He took the MS away with him. He did his utmost to move heaven and earth and the planets in Paternoster Row, but her could not get that novel bought. He went so far as to say to old What's-his-name, "My dear sir, if you only knew the young lady personally - the loveliest, the most charming in all the world!" "Oh!" said old What's-his-name; he would not buy the novel. Since then she has married - not Boodler. He does not visit at her new home.Follow me on Twitter @TinyApplePress and like the Facebook page for updates!

am in time and if he likes her then he will flirtin is always in your face kind of thing you no a guy likes you if he takes the time to chat to ya.

ReplyDeletejaipur call girls